By Aparajita Singh & Tarun Katoch, Dvara E-Registry[i]

Executive summary

In our quest to understand the financial needs of our partner FPOs’ farmers, Dvara E-Registry conducted a household survey with 175 farmers spread across four districts Buldhana, Pune, Ahmednagar, and Chandrapur in Maharashtra. The survey was divided into four parts and investigated different aspects of their agricultural and financial lives spanning across credit, insurance, saving and farmers’ outlook towards paying for agri-services which have till now been available free of cost provided that the paid services will be better suited to their requirements. We release these findings as a four-part blog series.

In this blog post, we discuss our findings on credit. Our conversations across the four FPOs provide evidence that farmers have credit appetite as well as willingness to pay if the market provides the right credit products allied with suitable agricultural services. Read on to know more.

Rural households have diverse sources of livelihoods. While most households depend on agriculture or allied sectors for their source of income; small shops, skilled professions, dairy, and labour comprise a significant portion of the population. A common thread across rural sources of livelihoods is their informal nature and consequentially the absence of monthly cash flows. The cash flows are often irregular, and the variations may range from being daily to being seasonal in nature. Most rural households depend on multiple sources of income for basic needs like food, shelter and access to essential services like health and education.

At Dvara E-Registry, a major component of our work is to understand the financial lives of the farmers we serve, in order to customize products according to their requirements. Agriculture remains one of the riskiest and most important business in modern times. Moreover, the concerned businesspersons or farmers in this case, do not have enough capacity to absorb these risks or tools to mitigate them in the event of an unforeseen occurrence. Yet, most financial products are not designed to cater to their needs, which brings us to some very pressing questions:

- Why aren’t there enough financial products to cater to such a large borrower base?

- What are the factors that contribute to the perceived riskiness of the borrower as well as the business?

We conducted a survey with 175 agricultural households across four districts from our partner FPOs to understand their overview and usage patterns of common financial tools like credit, insurance and savings.

Particularly for agriculture, we understand that riskiness of the business is contributed to three main factors[ii]–

- Time lag between investments and returns

- Volatility of commodity markets

- Underdeveloped financial markets

Understanding financial tools for rural and low-income households is important as, in the absence of these mechanisms, households mitigate risks by resorting to substandard mechanisms. For example, cultivating crops which are high-volume low return (cereals) as opposed to low volume high return crops (horticultural crops, cash crops). While diversification of assets for generating higher incomes and mitigating risks is encouraged, we note that low-income households use this technique to constantly protect themselves from falling into poverty or to fulfil repayment requirements of perennial short-term loans taken to counter liquidity crunches. This diversification in occupations can be seen where some investment in terms of time, money and labour is spread across farms, crops, dairy, and paid labour to ensure at least one source of income is available.

Through this survey, we aim to understand how a suitable credit product can help farmers break these cycles to elevate to higher-income scenarios and whether farmers are open to such a product.

A brief snapshot of the demographic characteristics of the respondents are as follows-

- 72% of the households had four-six members in the household, followed by 21% which had less than three members, and 7% of the households had seven to ten members in the households

- 83% of the households had one to two earning members, and 16% had three to four earning members.

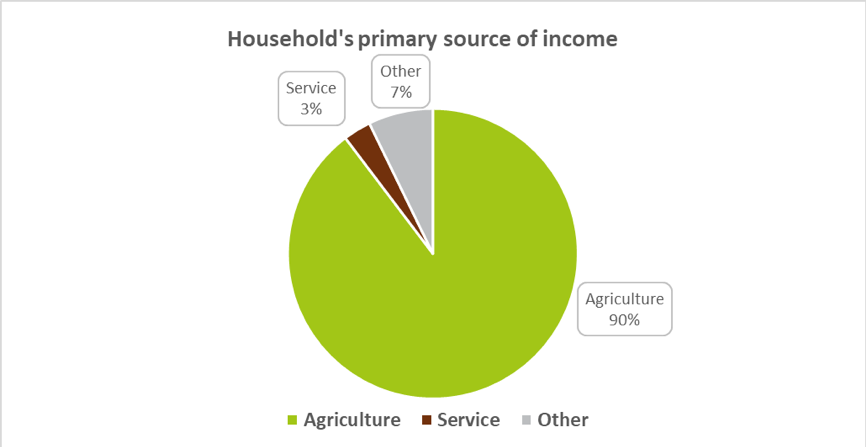

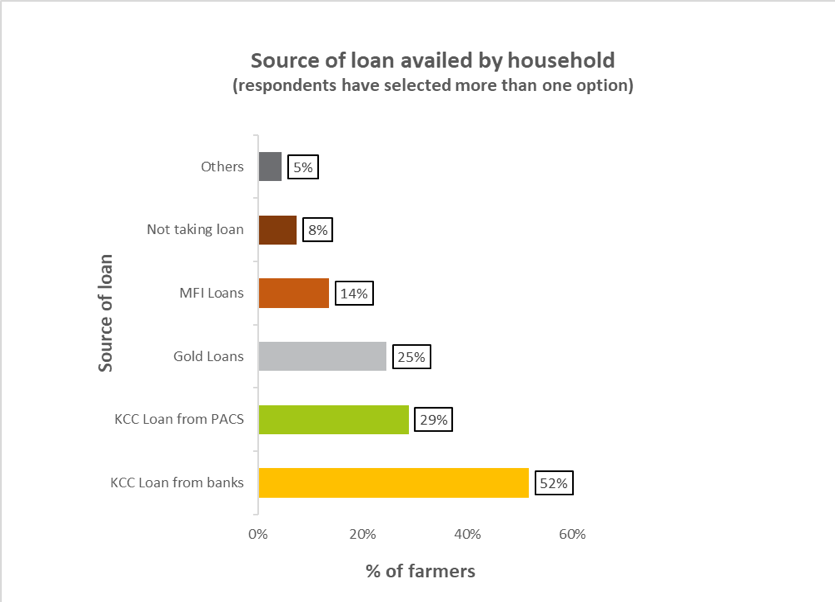

- For 90% of the households, agriculture was the primary source of income while there were rare instances of earnings via own business, dairy, Kirana stores, hair saloon, atta chakki (grain grinding machine), and so on.

Upon enquiring if the household was borrowing, more than 90% of the farmers were borrowing to meet their financial requirements. While more than half depended on KCC loans, the rest relied on gold loans, MFIs and other sources.

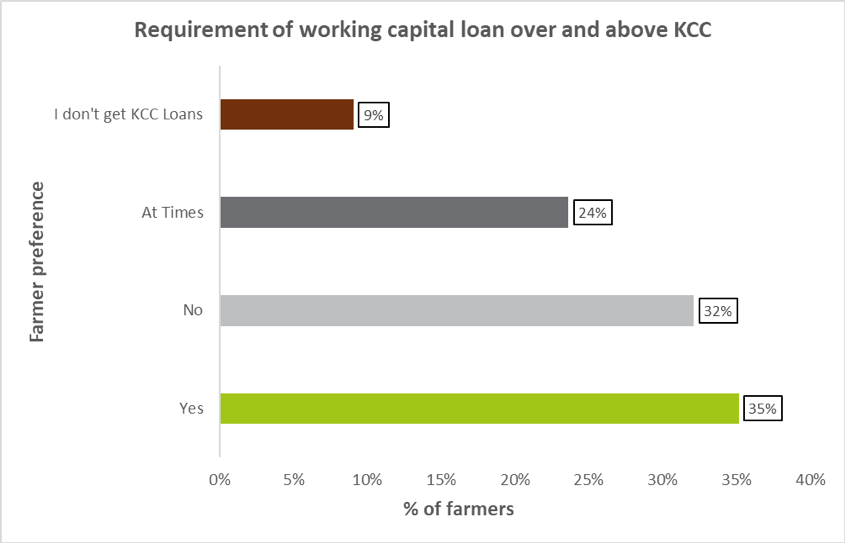

We learnt that more than half the respondents who were availing KCC loans felt that their credit requirements were not met.

For additional requirements, farmers usually rely on loans from local farmers groups.

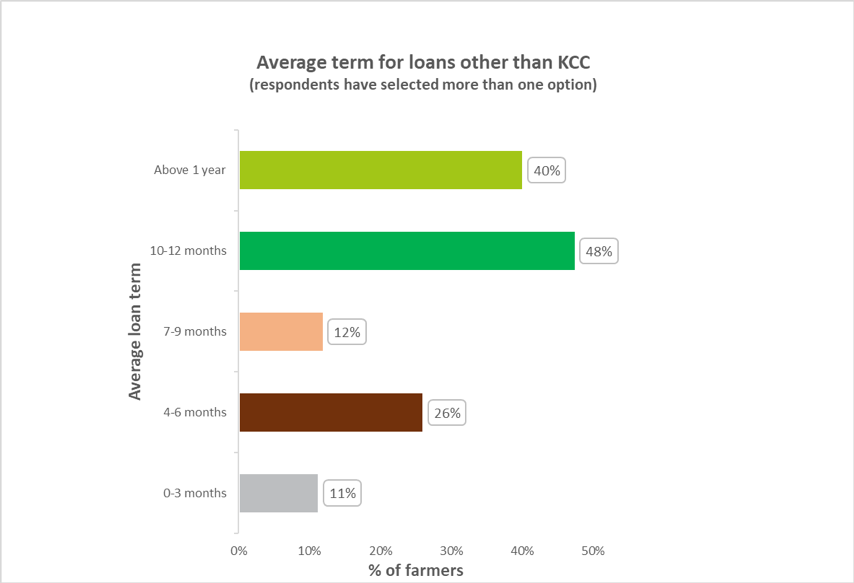

For most of the farmers, the duration of these loans is more than nine months. Still, we observe that a little more than a third of these farmers settle for short term loans which are less than nine months. Short term loans may be used for meeting urgent liquidity constraints as opposed to investments for better returns.

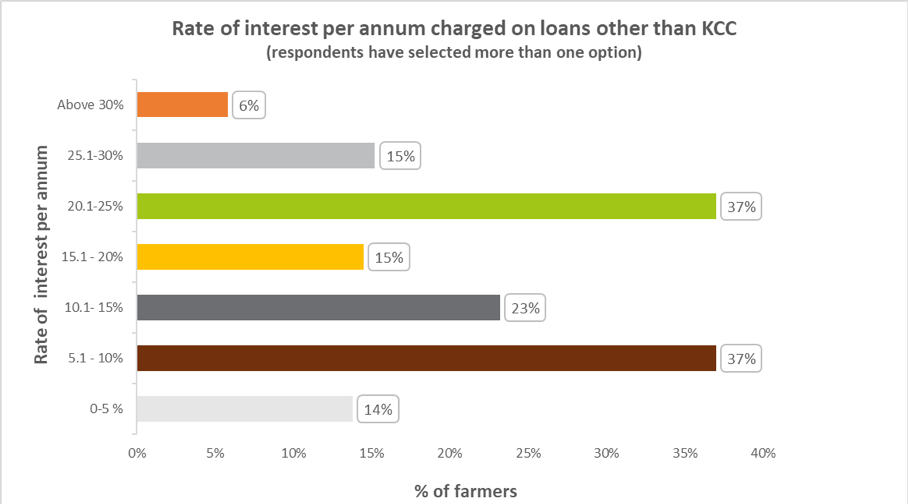

Majority of the farmers, depending on where they are borrowing from, are either paying in between 5%-10% or 20%-25% (rate of interest per annum) on loans. Generally, Kisan Credit Card (KCC) charges up to 5%, farmer groups charge in between 5%-10%, banks charge up to 15%, and NBFC MFIs charge above 15%. There are also instances of money lenders who charge as high as 60%.

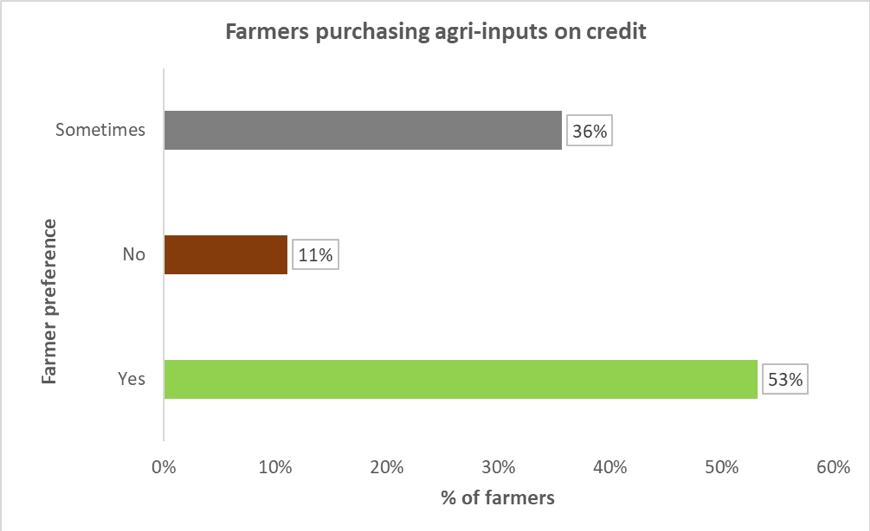

Though farmers do not cite borrowing from agri-input dealers, more than 50% require credit for purchasing agri-inputs.

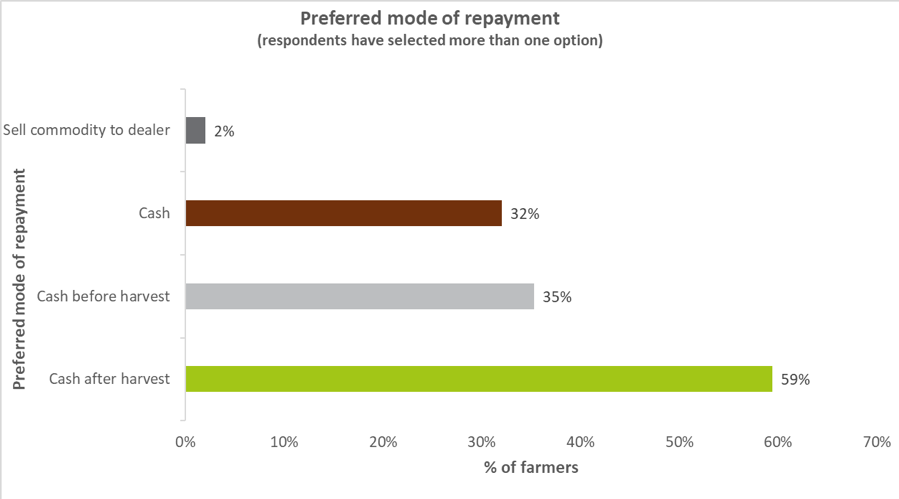

Most farmers in this region repay post-harvest even if they borrow from the dealer. This is contrary to the popular belief that they are bound to sell to the dealer for repaying the loan. Even among those who sell the produce to the dealer, they report receiving market prices for their produce.

Takeaways and product implications for lenders

We see that rural agricultural households have credit appetite and willingness to repay. There is a need to design credit products in such a way that farmers can invest these in productive agricultural activities which will offer better returns. Designing credit services for farmers which are well-suited for their financial and business needs will help them not only to repay the loans on time but also increase farmer incomes.

These credit products will add additional value when coupled with adequate agricultural know-how, access to relevant information about government schemes, agri-services, and price awareness across marketing platforms. Better farm productivity and price realization for farm produce ensure the ability to repay loans at market-determined interest rates. Since knowledge and access of such services are restricted to big farmers, some FPOs have now started channelling these same services to small and marginal farmers through digital platforms like Doordrishti by Dvara E-Registry. This helps de-risk these loans as not only do platforms like Doordrishti offer services to farmers that ensure they take the most profitable agricultural decisions but also help farmers monitor these loans.

[i] The authors thank Aastha Saxena for her assistance on the graphs. The authors also thank Nawale Navnath, Naresh Gaikwad, Vilas Mate and Ganesh Chormale on their assistance in conducting the survey.

[ii] Aggarwal, S. (2013). Commodity price risk and financing. In B. Ananth & A. Shah (Eds.), Financial engineering for low-income households (pp 172-180). New Delhi: SAGE India.